Some time ago, the Neapolitan artist told me about her new project but didn’t mention the repertoire. Still, just knowing a pianist of her calibre was taking on Schumann was enough to catch my attention. In my view, Mariani’s interpretations are like "smoother" readings—her playing is deliberate and softens the twists, edges, and abrasiveness of the music, guiding it into something more harmonious. Her choices of composers and pieces, including her own work, are deeply tied to the idea of memories and the inspiration drawn from specific places, real or emotional.

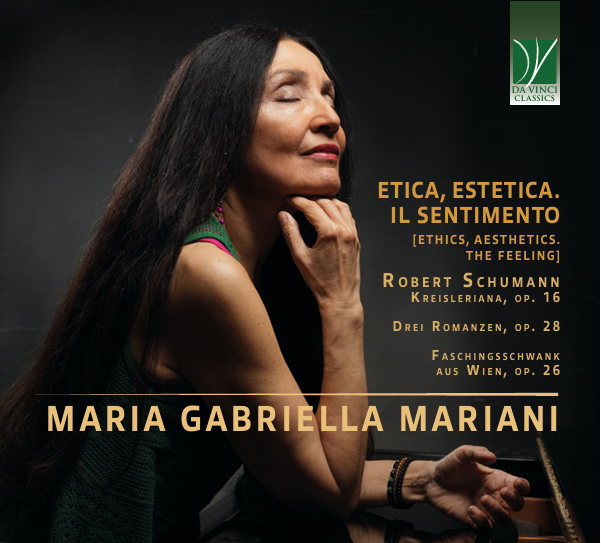

At this stage of my life and at my current age, I’m finally able to focus on recordings that truly engage me, rather than catering exclusively to the interests of other parties—composers, performers, publishers, or readers. As time advances, commitment becomes essential, and such commitment requires total immersion, channelling our reflections toward the very core of the work itself. That core is precisely what’s on offer in the newest album by Neapolitan pianist and composer Maria Gabriella Mariani for the Da Vinci Classics label, presenting a Schumann triptych: Kreisleriana, Op. 16; Faschingschwank aus Wien, Op. 26; and Drei Romanzen, Op. 28.

Some time ago, the Neapolitan artist mentioned this project to me without revealing her repertoire choices but merely knowing that a pianist of her stature—and especially with her distinctive interpretive Weltanschauung—had chosen to engage with Schumann set my antennae tingling. The reason is simple: in my view, Mariani’s interpretations position her as an “appianatrice” (if I may coin the term), in that her pianism is built, structured, sustained, and carried forward by a conscious drive to soften what is convoluted, angular, or harsh, unravelling a line that implies order, reconciliation, and a methodical unfolding nourished by both temporal and spatial dimensions. It is no coincidence that her choice of composers and works—and indeed her own compositions—always begins with the sacrality of Erinnerungen, that is, “memories,” so cherished and fundamental in Romantic doctrine, and with the need for a physical, geographic place—whether a fleeting glimpse or an emotional “postcard”—from which to draw inspiration and expressive commitment.

So far, her recording “tradition” had led her to program albums evenly split between her own works and those of other composers—even pairing her contemporaneous literary writings, published by various houses. In other words, sound perpetuated in words and vice versa. Against this backdrop, it was inevitable that sooner or later her path would intersect with that of the genius from Zwickau, who effortlessly reconciled musical and literary demands. And so, it has happened.

At that point, my curiosity cantered on her choice of Schumann pieces, and when I saw Op. 16, Op. 26, and Op. 28 in the tracklist, I was neither surprised nor, worse, disappointed—these three collections would give the Neapolitan artist free rein to enact the “ethical” and “aesthetic” processes indispensable to her interpretive approach (incidentally, the CD is titled Ethics, Aesthetics. The Feeling, which to me reads like a wedding invitation without knowing what kind of guest I’ll be). Let’s begin with that title, paying close attention to its punctuation: ethics and aesthetics are joined by a comma and sealed with a period, while feeling stands alone. In Mariani’s vision, the result is unmistakable—a kind of soul‐equation showing that ethics plus aesthetics (Kierkegaard may not have approved, but let’s pretend he did) equals feeling. With this Schumann album, our pianist has laid her cards on the table, thrown open the door (at her own risk) to let us read her through her sound, because the ultimate, almost eschatological principle that drives and sustains her is the ability to find, discern, and ultimately reveal the very “feeling” in things.

Let me be clear: here we’re talking about “feeling,” not “sentimentality.” Of course, we need to define, delimit, and even rationalize what we mean by “feeling.” It’s a bit like Louis Aragon’s wry remark: “Who’s there? What? Infinity? Wonderful—let it in!” For Mariani, feeling is, at its core, infinity itself. Hardly a trivial matter. And, transposed into a poetic–theological context, it becomes the closing line of Dante’s Commedia—“L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle”—the very principle that sustains the existence of things, of our subjectivity, and of the objects beyond.

From this perspective, feeling in its totality—not just its answers but especially its questions—also serves a “smoothing” function, much like Maria Gabriella Mariani’s pianism. In the album’s liner notes, which she penned herself, she writes: “I confess I’ve never been drawn to Robert Schumann’s psychological issues; it would be like justifying Leopardi’s pessimism by pointing to his physical ailments.” To her, pathology—whatever its form (and by “pathology” she means that extraordinary force that unerringly upends the ordinary to spark the creative process)—is irrelevant. What matters is “care,” not as a therapeutic response to pathology but, whether consciously or not, as Heidegger’s notion of Sorge: not a psychological construct, but the fundamental ontological structure of Dasein’s being-in-the-world—an original openness to things and others.

Through her pianistic interpretations, the Neapolitan artist aims to open both herself and her listeners, regardless of what precedes the actualization of being-in-the-world and all that this entails.

This is why her performances become an intimate act—if by intimacy we mean the supremacy of an instinctive innocence that can lurk within things. On an artistic-interpretive level, hers is a rebellion against being-for-death.

That’s also why she breezily dismisses Schumann’s troubled psyche, as well as the physical “scribble” that was Leopardi. “To purify from defacement” seems to be Mariani’s artistic motto—revealing on the surface what was already there, opening where there was once wrongful closure—and it leads her to proclaim, echoing the philosopher from Meßkirch, “When I play, I am the others.” Perhaps this very act of becoming “the others” compelled her to exclude herself, choosing not to include her own compositions on this disc but offering herself exclusively to others. And here, at last, we arrive at her Schumann.

First up is the Kreisleriana, with which she delivers the opening slap (sometimes even innocence demands a forceful hand). It’s a slap in the old-fashioned sense, when high-spirited duels were settled by one challenger throwing down a glove or landing a well-aimed cuff on the opponent’s cheek.

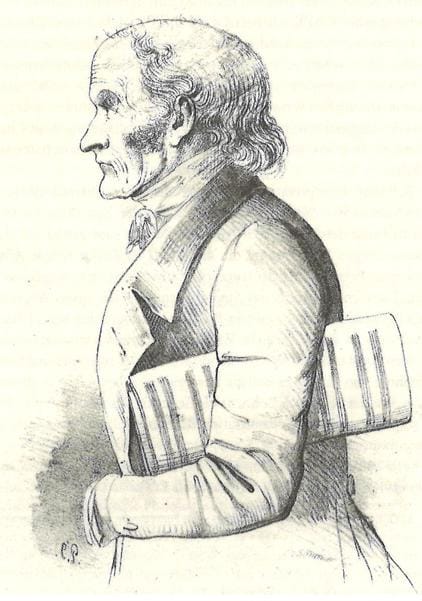

Mariani’s zeal for duelling is clear in how she approaches this immortal score, confronting it under the premise I mentioned earlier—namely, refusing to let the psychological upheavals that shadowed Schumann’s life since youth dictate her interpretation. To be fair, one cannot wholly fault Friedrich Wieck for opposing Clara and Robert’s marriage with every fibre of his being, given the imbalances and shadows the young composer displayed as his pupil.

Even when faced with a piece like Kreisleriana—which, beyond stirring and seducing music lovers, has drawn psychiatric and psychoanalytic study as a sort of seismograph, recording every sudden shift, abrupt deviation, lightning ascent, and abyssal descent that emerged in Schumann during those feverish four days of spring 1838 when he composed the eight movements of Op. 26.

If Maria Gabriella Mariani isn’t interested in all that—or at least doesn’t consider it binding for shaping a more genuinely receptive framework for her interpretive identity—it’s because, for her (and not only in the Kreisleriana but also in the two other works on the CD), what truly matters is presenting a sound that is emancipated and purified from everything extraneous to its emergence. She even highlights another crucial factor in her liner notes: Schumann “finds in Bachian form and composure a refuge to strive for,” and Mariani is equally intent on exploring “his logic, his way of composing that lends piano pieces a symphonic dimension.” Given this, it’s no surprise she describes the Kreisleriana as stamped with “a dramatic, indeed epic, imprint.” Listening to her performance confirms it: every emotional upheaval is met with an extreme composure—not as rigidity or mere formal constraint, but as a balancing force across the work’s arc, from the most “disturbed” segments to the calmest, all in deference to that Bachian logic governing Schumann’s pianism (listen to the seventh segment, Sehr rasch–Noch schneller–Etwas langsamer).

Mariani furthermore seeks to magnify the moods, flavours, colours, and scents this work inevitably projects—a lesson, she admits, learned from Aldo Ciccolini, who in the French tradition emphasized precisely those qualities that often recede into the background in the German school. The Neapolitan pianist thus pursues a canon of beauty, harmony, smoothing, and “diplomatic” balance among the eight movements, intentionally avoiding the schism or traumatic fragmentation between opposites—as if Florestan and Eusebius had shaken hands only to sit down later at a peace table.

It also becomes unmistakably clear that Mariani is driven by an uncompromising search for absolute clarity of sound—a desire to tip the scales toward a more classical, Apollonian projection of what musical structure can offer the listener, as though seeking in the work of a twenty-eight-year-old composer a gesture of wisdom. Even in moments of stark dynamic or timbral contrast—consider the Sehr lebhaft of the fifth segment—her reading remains resolutely “constructive,” designed to bring forth Schumann’s compositional genius.

Finally, there is the abyssal leap of the Schnell und spielend, where the performer must dare to peer over the void without succumbing to vertigo. Mariani captures this in a kind of “alarmed contemplation” of the chasm beneath her, leaning heavily on the agogic concept of Spiel that suffuses this finale.

Chapter: Faschingschwank aus Wien, Op. 26 (1839), which the Neapolitan artist literally dubs “brilliant.” This work has almost nothing to do with Op. 9. In the latter, the mask motif is overtly foregrounded—with all its unconscious and subconscious resonance—whereas in Op. 26 the whole affair feels far more elusive and conflicted. By then Schumann was nearing thirty and had realised that his purely, heroically “Romantic” outlook could no longer sustain itself in everyday life. Standing on the brink of his stormy marriage to Clara, he knew he had to settle down, tame his passions, and embrace a measure of bourgeois respectability.

It was also the twilight of his exhilarating decade devoted exclusively to the piano, since 1840 would be dedicated, splendidly, to Lieder. So, Op. 26 represents his moment of reckoning—what more could he still draw from the keyboard? Here, he clearly pivots back—albeit sweetened and refracted through his compositional sensibility—toward a kind of “Classicism.” If we understand Classicism as the five-movement architecture of Faschingschwank aus Wien, Schumann himself even called it a große romantische Sonate, albeit one utterly divorced from Beethoven’s late-period sonata concept and, above all, from Schubert’s model. For Schumann, the sonata was more like the Befana’s stocking, into which he could pour all his musical ideas without feeling bound by the strictures of the Viennese tradition. And in Op. 26 those ideas manifest as distinct “characters,” not “masks,” since masks, by that point, had long since fallen away.

Our interpreter was keen to stress that her reading is “conceptual” in nature, immediately evident from the very first bars of the opening Allegro, where the structure isn’t unravelled but rather “anchored” in a clear, incisive, driving, and effervescent timbre. This mood asserts itself from the outset and imprints the DNA of the entire performance indelibly. In my view, such conceptual rigour is necessary because the compositional framework here is, so to speak, “organic” (an admittedly clumsy term, but it conveys how, on repeated listening, one perceives the formal balance and volumetric integration of ideas and characters working like a finely oiled mechanism).

Moreover, Mariani succeeds in revealing that veil of melancholy—a subtle, bitter nostalgia—that governs not only the Romance but infuses the entire work. Beneath the effervescent surface, one always senses sharp, almost “gasping” accents (listen for the characteristic jolt in the Intermezzo). Even the Finale resists any temptation toward a convulsive, ravenous frenzy; its palpitation is delivered with disciplined rigor (with Bachian echoes…) that Schumann himself, five years earlier, would scarcely have sustained in the same way.

In the album’s tracklist, the Three Romances, Op. 28, are placed between the Kreisleriana and the Faschingschwank aus Wien—perhaps Mariani’s way of carving out a joyful oasis (a rare word in Schumann’s world), clear, radiant, and open to a future that is at once hope and promise. She even describes their sequence as “narrative.” It may surprise listeners less versed in Schumann’s piano output that he himself ranked Op. 28—alongside the Phantasiestücke, Op. 12, the Kreisleriana, and the Novelletten, Op. 21—as his finest keyboard works. I believe Mariani’s pianistic identity finds its ideal reflection in these three pieces: for the elegance they exude—especially in the second Romance, Einfach—and for her gift in projecting the pointed rhetoric of the third without reducing it to a charming yet hollow march. The end result perfectly embodies her intent: to strip Schumann of his cumbersome, “pathological” biography and restore to his music a fairytale quality—another realm dear to Mariani—guiding the listener back to that essence of innocence, those “lost horizons” in their purest form that the Zwickau genius’s piano can reveal.

Giovanni Caruso’s recording captures Mariani’s Steinway with crystalline clarity. The dynamic range, though slightly restrained in sheer power, feels entirely natural and more than sufficiently agile. In the stereo field, the piano sits centrally between the speakers, a touch forward toward the listener, yet without sacrificing the height or breadth of its tone, which radiates well beyond the confines of the studio. The tonal balance is impeccable, with the mid-low and high registers equally well represented, and the level of detail is satisfyingly tactile, lending the instrument a convincing three-dimensional presence.

Andrea Bedetti

Robert Schumann – Ethics, Aesthetics. The Feeling

Maria Gabriella Mariani (piano)

Da Vinci Classics CD C01069

Artistic rating 4,5/5

Technical rating 4/5