Disc of the month October 2025

The enterprise undertaken by the duo Cantar alla Viola — made up of Jordanian-born, naturalized American soprano Nadine Balbeisi and Spanish viol player Fernando Marín — together with the Da Vinci Classics label, is a most commendable and noteworthy undertaking: together they have produced the first modern, complete recording of a musical monument of the German Baroque repertoire, namely Jacob Kremberg’s Musicalische Gemüths-Ergötzung (that is, Delight of the Musical Soul), issued across no fewer than three CDs.

This collection, comprising forty arias with basso continuo accompaniment by the German composer and published in Dresden in 1689 by the publisher Mathesius, stands as a unique example of how musical practice at the time could function flexibly — performable within the domestic walls of a household, beneath the vaults of a church, or in a small civic hall — and whose purpose was to edify, comfort, and entertain small communities. Thus, it served an aim at once spiritual and social, capable of excavating the individual while simultaneously engaging a group of listeners.

Personally, I have always regarded this little book as a kind of “treatise in sonic sociology,” a methodical and purposeful demonstration of how music, under the influence of Protestant thought and anthropological conception, became a remarkable vehicle for spreading the Protestant creed both in its religious form and in its guidance for everyday life in relation to oneself and others. This, of course, as we shall see, in no way detracts from the artistic beauty of its pages.

But before tackling this work and the recording, let us first establish who Jacob Kremberg was, a name little known to most. After leaving his native Warsaw, Kremberg enrolled at the University of Leipzig in 1672 and in 1677 became a chamber musician to the administrator of the chapter of Magdeburg, before entering the Royal Swedish Chapel in Stockholm from 1678. Subsequently, from 1682 until 1691 he served as a contralto singer at the Electoral Court in Dresden, where he received an annual salary of three hundred thalers under the vice‑kapellmeister Nicolaus Adam Strungk. From 1693 he directed, together with Johann Sigismund Kusser, the Hamburg Opera at the Gänsemarkt, writing, among other things, the libretto for Georg Bronner’s opera Venus or Love Triumphant in 1694. Later, following a bitter quarrel with Kusser, he hastily left Hamburg at the beginning of the following year, leaving behind substantial debts.

Kremberg then worked for two years at the University of Leiden, where he was probably the teacher of the Scottish composer John Clerk of Penicuik. It can be supposed that this appointment eased his move to England, since from November 1697 he organized a series of concerts in London at Hickford’s Dancing School. In the English capital Kremberg built an excellent reputation, helped by his leadership of an ensemble of first‑rate musicians. That fame enabled him in 1702 to become music teacher to the children of Lady Grisell Baillie of Mellerstain House in Berwickshire. Moreover, in the final phase of his life, in April 1706 he even held a post at the English court; he died in September 1715 and was buried in St. Anne’s Church, Soho.

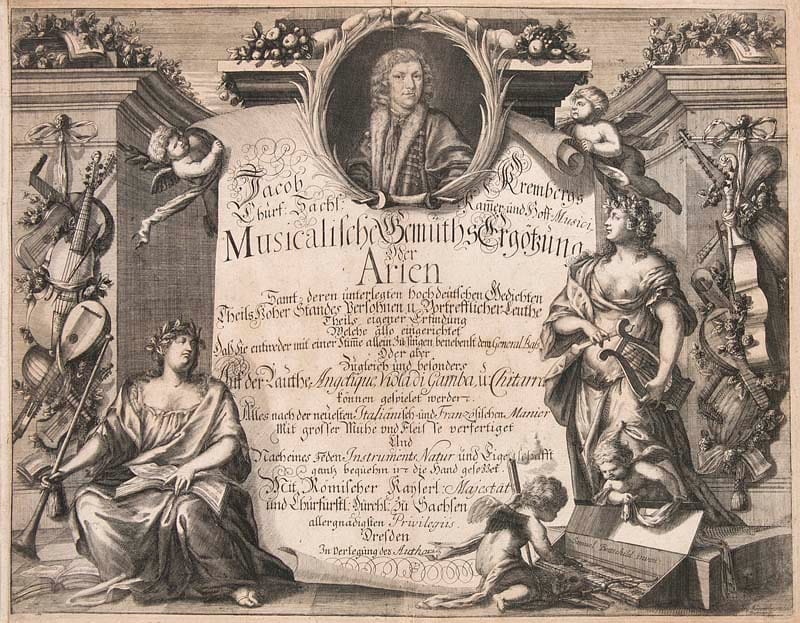

It is worth noting that Kremberg was one of the few composers to write for the angelica, a particular plucked instrument of the Baroque period with sixteen strings and characteristics of the lute, harp, and theorbo, which the Polish composer listed among the instruments suitable for accompanying the songs in the Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung.

As for this work, we know that Kremberg created it in Dresden while serving as a contralto at the local Electoral Court. Concerning the Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung and its spiritual and social aims, which, as noted, are shaped by a Protestant outlook, it is also true that no explicit documentary evidence definitively proves Kremberg’s confessional affiliation; yet all the biographical data that have come down to us agree on the places and posts he held, which point to his placement within the Protestant world. This is because the composer was active in Leipzig, Halle, Magdeburg, Dresden, and in the operatic circles of Hamburg — centres closely connected to Lutheran tradition and the Protestant courts of the Holy Roman Empire. Moreover, he first studied at Leipzig (a university linked to Lutheran culture) and composed arias and vocal music in German consistent with the sacred and secular Protestant taste of the period.

Now, if one considers the full title of Kremberg’s work, one can obtain further details or at least become aware of the musical features that make it wholly distinctive. The title reads verbatim: Musical delight for the soul, or arias together with their accompanying poems in High German, partly by persons of high rank and distinguished persons, partly of my own invention; which are arranged so that they can be sung with a single voice, together with basso continuo, or performed simultaneously and especially on lute, angelica, viola da gamba and guitar. All executed with great care and diligence according to the latest Italian and French manner, and made perfectly suitable to the hand according to the nature and characteristics of each instrument, Dresden, 1689.

An especially important aspect is that, as stated in the title itself, the accompaniments indicated — beyond the general bass — are those that can enhance the singing, namely “lute, angelica, viola da gamba and guitar.” Now, particularly with regard to the recording under discussion, the viol part, arranged in tablature, has proven to be a unique and invaluable musical example of the “practice of singing to the viol” in seventeenth‑century Germany and for this reason was chosen for the present recording both in the forty arias where it accompanies the voice and in their solo instrumental versions.

Concerning the Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung, which has a format of 34 × 41 cm, it therefore contains forty arias (38 for solo voice and 2 duets); all the arias are written for Cantus (soprano), except for numbers 22 and 33, both indicated to be sung by Altus. In this recording Nadine Balbeisi chose to perform aria no. 22 as indicated in the score, while aria no. 33 with the voice set an octave higher. The two duets (specifically arias 6 and 23) are composed for two soprano voices. All forty arias are in strophic form with German texts, ranging from a minimum of three to a maximum of ten stanzas.

As for the authors of these texts, we know only that fifteen poems can be attributed to Kremberg himself (arias nos. 1, 3, 7, 8, 10, 13, 16, 17, 19, 22, 23, 33, 36, 38, 39), while the remaining twenty‑five texts are by anonymous authors.

Focusing on the themes treated in the texts (the booklet provides a link to access the original texts and their English translation), one can observe how sacred and profane dimensions intermingle. The poems alternately address love, fortune, devotion, hope, and despair, thereby creating a divided universe marked by a clear fault line: on one side the exaltation of carpe diem, urging the pursuit and surrender to the pleasures the world offers; on the other the vanitas mundi, which forces the “sinner” to confront the inevitable transience of things and, consequently, death itself. The most frequent subject is love, which can in turn be divided into two distinct spheres — love that is returned or aspires to be returned (arias nos. 19, 21, 23, 24, 29, 32, 36, 37) and unrequited love (arias nos. 1, 13, 16, 20, 25, 26, 28, 30, 33, 35, 38) — plus aria no. 27, in which a poet asks whether it is worth loving at all.

Another recurring theme in the Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung’s poetry is the concept of time, treated as an explicit admonition to humankind, notably in arias nos. 14, 34, 39 and 40, which even invoke the falls of Egypt, Rome and Babel as edifying examples. Naturally, religion and its dogmas contribute strongly, as shown in arias nos. 2, 3, 6, 9, 10, 11, 22 and 31, which stress the importance of faith, upright living and moments of hope, as well as the consequences one can suffer, represented by images of storms, torments and despair. Specifically, despair and faith are portrayed most vividly in certain arias (for example nos. 7, 15, 17, 18), with striking depictions of Christ’s suffering, especially in aria no. 4, which paints scenes of blood flowing from his veins, and in aria no. 8, where bearing one’s cross is presented as a higher good, that is, to save humanity from its pains and sins. Finally, arias nos. 5 and 12 express the ultimate desire for death and salvation, with explicitly eschatological aims.

An especially significant aspect, as Fernando Marín himself explains in great detail in the booklet notes accompanying the three‑disc set, is the use of the bowed instrument. In this recording the Spanish gambist makes use of two viols he built himself: a 1693 copy of a Franz Zacher used on the first two discs when accompanying Nadine Balbeisi’s voice, and a 1683 copy of a Mathias Repensburger, with which he performs as a soloist on the third disc.

The importance lies in the practice of scordatura, that is, a technique for bowed instruments involving tunings different from the standard in order to obtain unusual effects, vary the instrument’s timbre, or enable the execution of particular chords. Scordatura was adopted at the end of the sixteenth century for the lyra, the viola da gamba and the bowed lyre when they were used as solo instruments or in combination with others and to accompany polyphonic or chordal singing. This gave rise to a distinct repertoire that extended beyond the usual polyphonic vocal works into the early seventeenth century, when a virtuosic voice was accompanied by continuo harmonies in chords. Fernando Marín notes in the booklet that some of the scordaturas appearing in Jacob Kremberg’s Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung do not belong to the scordaturas known from that period, which suggests that many have been lost and that only the most widely used tunings were transmitted.

Another aspect to bear in mind, precisely because of the importance of this work, is that it represents one of the most brilliant and essential examples for understanding and appreciating the practice of pairing singing with accompaniment on a bowed viol — a tradition that begins in the Middle Ages and continues into the early Baroque, a practice known as “singing to the viol.” Documentary evidence for this practice is almost entirely lacking because musicians typically notated and created their own parts without taking care to preserve them. To gauge the spread of “singing to the viol” we can, however, rely on what Baldassare Castiglione writes in his famous treatise The Book of the Courtier, published in Venice in 1528. According to the celebrated Mantuan humanist, among the musical styles a courtier should cultivate, the best was precisely the art of singing with the viol, intended to enhance the sweetness expressed by the solo voice.

Therefore, despite the prominence given to it in its time, it is not surprising that only a very small number of testimonies have reached us concerning the practice of transcribing viol accompaniments for the voice. Those testimonies come chiefly from England from the seventeenth century onward — for example Robert Jones’s The Second Booke of Songs and Ayres (1601), William Corkine’s The Second Book of Ayres (1612) and Robert Tailour’s Sacred Hymns (1615) — whereas from Germany the only example may well be Jacob Kremberg’s Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung. As the full title of that work shows, the musical accompaniment is presented in a way that, in addition to the vocal melodic line, includes tablatures for the instruments listed, thus offering a variety of interpretative possibilities. These different tablatures prove to be exceptionally precise and accurate, since they indicate the exact notes of the harmony and the ornamentation.

To explain more clearly the practice of scordatura as applied in that era, the duo of performers also provide precise particulars, which of course will be understood by those familiar with the theoretical procedures of the technique but are nonetheless revealing for grasping the complexity of the process, a complexity further intensified by the fact that musical cultures such as the English, French and German each contributed their own additions and harmonic refinements. In any case, Fernando Marín and Nadine Balbeisi chose a set of tunings for the three‑CD recording designed to highlight and emphasize “the clarity of the harmony between voice and instrument and the intelligibility of the poems’ texts,” precisely to allow the “effective transmission of the message of these delicate and complex pieces.”

In light of these few indispensable details, one can only imagine the research, interpretative work and decisions required of the duo Cantar alla Viola to align the vocal emission properly with the sound of the viola da gamba. For this reason their performance deserves above all great respect: listening to these three discs requires time, a lot of time in an age like ours that no longer has any. Whoever chooses to venture into this wonderful undertaking should know that each aria, whether in the “singing to the viol” version or in the purely instrumental one, is a treasure chest to be contemplated with restraint and deep awareness. Beyond those who love early music and are therefore accustomed to its rituals and its “sacrality,” one must not forget that the Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung is a gateway to a temporal, social and cultural dimension which, if properly approached not only through artistic transmission but also through historical study, allows its full depth to be assimilated.

The more I get to know the duo Cantar alla Viola, the more I realise that only Nadine Balbeisi and Fernando Marín could have undertaken and completed such a project. If scholarly research, study and assimilation in the field of musicology are beyond the reach of many in terms of attention, passion and expertise, the interpretative task is even less so, for here we face a vocal and sonic polyhedron that must be unraveled and built brick by brick, aria by aria, each continually changing in its stylistic affiliation and in reflecting imperatives belonging either to the secular or to the spiritual sphere, to sacred love or to the profane. Flexibility, intensity, fidelity, immersion, rigour: these are the demands of this monumental work of the German Baroque, especially given that it is here restored to its entirety for the first time.

Thus, if Nadine Balbeisi confirms herself as an almost ideal voice to embody (to use the verb “to sing” in relation to this work would frankly be reductive) the Gesamtschau of an era in the whirl of passions, contemplations, admonitions and redemptions — and one must note that the high and very high register is mercilessly required and solicited — she does so with exemplary naturalness and a sense of theatricality, in a constant play of changing moods and stylistic nuances. Fernando Marín, for his part, is not only a “solid rock” supporting her with an accompaniment of sonic psychology and an inexhaustible palette of nuances, but on the third CD he offers readings of these arias that become a powerful magnifying lens capable of probing and projecting the mystery of sound itself, thanks to an interpretative mastery of rare beauty and effectiveness.

October album of the month for MusicVoice.

The sound capture by Alessio Balsemin at the Convent de les Arts d’Alcover in Tarragona, together with the mastering work by Miguel Ángel Barberá, in no way diminishes the beauty and feeling radiating from this sumptuous artistic reading. The dynamics are more than adequate in terms of speed, energy and the much‑needed naturalness expressed especially through microdynamics (I refer to the timbral nuances articulated by the voice and the viola da gamba). The soundstage is equally excellent, with the two performers easily located by a reconstruction that places them at the centre of the speakers in a somewhat forward position that feels natural and serves the recording’s discursive and theatrical dimension. The tonal balance shows no smudges of any kind, always delivering a focused blend between voice and instrument across the middle‑low and high registers. Finally, detail — aided by a considerable amount of silence surrounding the two performers — makes listening far from tiring, even given a running time exceeding three hours, at least for the brave who choose to tackle the complete set in one sitting.

Andrea Bedetti

Jacob Kremberg — Musicalische Gemüths‑Ergötzung

Nadine Balbeisi (soprano) — Fernando Marín (viola da gamba)

3CD Da Vinci Classics C01089

Artistic rating 5/5

Technical rating 4,5/5