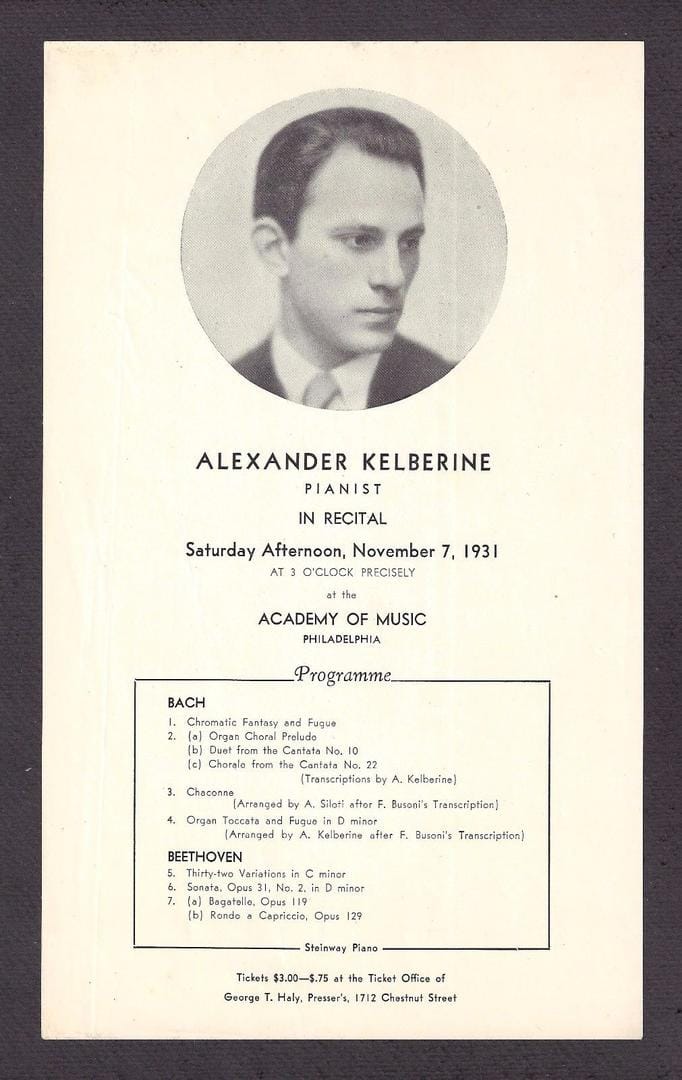

In the past, during one of my lectures, I happened to mention the almost entirely unknown—at least to the general public—figure of the Russian‐born American pianist Alexander Kelberine, who had studied with Ferruccio Busoni in Berlin and who took his own life at the age of thirty‐three in New York in January 1940, after years spent in the grip of depression. If his name still occasionally surfaces, it is precisely because, as a victim of the “dark sickness,” to borrow Italian writer Giuseppe Berto’s phrase, he programmed recital programs composed exclusively in minor keys throughout his performing career, especially in its final phase.

And if I’m to be perfectly candid, personally—while neither suffering from a depressive disorder nor entertaining suicidal thoughts—I find the minor mode, particularly when articulated and presented at the piano keyboard, far more compelling and fascinating not only for its intrinsic musical qualities but also for its speculative and reflective possibilities. I have always paired a transcendental conception of thought with the major mode, whereas I unstintingly associate the minor mode with the immanent realm: a profoundly deep pool into which both performer and listener/critic may plunge to explore its depths at leisure. For anyone brave enough to tackle a challenging yet invaluable study, I recommend the musicologist Rita Steblin’s A History of Key Characteristics in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries (University of Rochester Press, 1996).

So, when I was invited to listen to—and duly reflect on—a very recent Da Vinci Classics release featuring the Sicilian pianist Carmelo Giudice performing six Mozart pieces (plus two bonus tracks available for download on Edmondo Filippini’s label website), I leapt at the chance. The CD’s title, Masterpieces in Minor Keys, leaves no doubt: every composition belongs to the realm of minor tonality. It’s all too easy, in fact, to link the name of the great Salzburger and the complexity of his output to the idea of “otherness”—that which lies hidden in the folds of the Self and is brought to light through the mystery of artistic creation. And although Mozart has never been the subject of a psychoanalytic biography on the scale of Maynard Solomon’s Beethoven, analysts of the stature of Sigmund Freud (who notoriously disliked music save for certain works—unsurprisingly, a number of them by Mozart) and Melanie Klein have nonetheless turned their analytical focus to Amadé.

Even Carmelo Giudice, in a sense, set out to do the same—albeit from a strictly musical standpoint—by taking as his model (and, if we wish, bringing psychoanalytic dimensions into play) a group of piano pages we might term “Oedipal.” He begins with the truly unconscious eruption of the Piano Sonata in A minor, K. 310, which, in its closing bars, symbolically recapitulates the ill-fated third journey undertaken by the Salzburger genius in Paris from March to September 1778. On that occasion Mozart was not accompanied by his father—detained in Salzburg at the behest of the oppressive Archbishop Colloredo—but by his mother, who suddenly died in the French capital on July 3 after a brief illness.

In short, it was the same old story, with the young Mozart forced to travel all over Europe to make himself known, to look for work, to earn money (which would become an obsessive element, especially once he had settled permanently in Vienna), becoming fond of and in tune with some people, especially the Italians and their music, or decidedly antipathetic and artistically repulsive, especially the French and in particular the Parisians (whom he called “donkeys” in a letter addressed to his father).

Confronted with these positive or negative reflections upon his ego, Mozart chose to re-mediate them through his art—that is, to reconcile the centripetal impulses of his complex inner life with the centrifugal forces of the external stimuli he encountered. In this respect, the Sonata K. 310 is simply paradigmatic. On one side lies the trauma of his mother’s sudden death (I shall spare us any superfluous psychoanalytic theorizing); on the other, the exhilaration sparked by new technical-musical discoveries, born of his enchanted encounter in Augsburg with Johann Andreas Stein’s pianos—then celebrated as among the most advanced prototypes of the emerging hammer-action instrument. This dialectic of inner and outer forces culminates in the Sonata in A minor, a work both born of tragic trauma and sculpted by the technical possibilities the new pianoforte afforded. We must also recall the profound impact on the twenty-one-year-old Mozart of Johann Schobert’s tempestuous, fiery style—a German composer all the rage in Paris, where he perished at thirty-two alongside his wife after consuming a fatal dish of poisonous mushrooms.

The explosive admixture of these ingredients erupts in the Sonata’s celebrated opening movement—an Allegro maestoso—sculpted on the one hand by harmonic dissonances and on the other by a march-like rhythm laid out in the incipit, upon which a stark thematic clash is mounted: a crash in which the aforementioned march collides with a neurasthenic semiquaver flow. This gives way to a “dissociation” between the insistent left-hand figurations and the visionary polyphonic progressions of the right hand, culminating in a recapitulation that mediates the second theme in the minor mode.

If one listens closely to the Andante cantabile con espressione that forms the central movement, one cannot fail to notice that here too the underpinning—offered by a Galant model of ornamented melody over an Albertin bass—serves fundamentally as a crust which, once torn away, still reveals the pus, so to speak, of deviation, of divergence, of anomalous meanderings born of the attempt to process mourning through a new, dark theme. Within it, multiple traces pursue one another, driven by the keyboard’s varied registers and materialized through dissonant figurations.

Nor does the concluding Presto succeed in overturning the situation by presenting, so to speak, a “sunny” guise despite its ostensibly radiant opening; here Mozart transforms the Rondo into an obsession—evoking the image of a hamster ceaselessly running in its cage’s wheel—since the ensuing episodes (the wheel) are all derived from the construction of the same rhythmic figure of the refrain (the compulsive obsession on display). It is as if a neurotic apparatus had at last found its stability, its coherence, the squaring of the circle (once more the vision of a turning wheel), through the simulacrum of an order capable of governing and disciplining inner disorder.

Beyond K. 310, Mozart composed only one other minor-key sonata: the C minor Sonata, K. 457, completed six years after the A minor. By then he and Constanze were settled in Vienna, residing on the third floor of Johann Thomas Edler von Trattner’s palace—a prosperous bookseller and publisher whose young wife Thérèse was one of Amadé’s favourite pupils. On September 21 of that year Constanze gave birth to their son Carl Thomas, baptized the same day with von Trattner as godfather. Yet just eight days later—eight—Mozart, his wife, and their newborn abruptly moved out. Why? Did they choose to leave, or were they evicted by their landlord? We don’t know for certain, but the Italian dedication Mozart inscribed on the Sonata—“per la Sig.ra Teresa de Trattner dal suo umilissimo servo Volfgango Amadeo Mozart”—shortly after composing it on October 14, and the composer’s well-documented amorous escapades suggest that von Trattner, now likely cuckolded, demanded a swift clearing of house to restore order and decorum.

Trauma born of libidinous impulses turned to guilt and affliction; nostalgia tempered by remorse: these are the new raw materials with which Dr. Jekyll/Mozart seeks to atone for Mr. Hyde/Mozart’s satyriasic excesses in a sonata where pain and drama—bordering on tragedy, at least temporarily—must be sublimated and systematized. The result is another masterpiece and a further page in which Mozart kicks the “amorous butterfly” facet of his character under the looming lash of the future Commendatore, already stalking his mind long before The Marriage of Figaro takes shape two years later. In short, we’re already immersed in the realm of opposites and their possible reconciliation—the very core of Mozartian DNA—and this is vividly demonstrated in K. 457, a veritable festival of pathos and, at its opposite, fatalism that thwarts realization (right, Amadé? right, Thérèse?). Throughout the work one encounters a brilliant succession of contrasts built on a dialectic of antithetical principles: a constructive oxymoron that unfolds through virtuosic technique—sprinkling gasoline on the fire and propelling a drama that oscillates between the tragic outer movements and the nostalgic metastasis of what-might-have-been (the central movement). All of this proceeds in a parade of masterful register contrasts, futuristic resonance effects, “Beethovenian” octaves, and a hand-crossing cantabile exalted by the right hand.

Leaving the sonata realm to turn to that of the Fantasia, I cannot help recalling—still under the sway of the principle of transference—a scene from Miloš Forman’s flawed yet cunning film Amadeus: Mozart, at a masked fête where Salieri sits incognito at the harpsichord, mocks his style in a childish parody. At the climax of this prank, Mozart unleashes a thunderous fart, provoking uproarious laughter from everyone present save the mortified composer himself. Beyond the age-old vulgar caricature of the “eternal child” Mozart—so dear to Goethe—it’s striking how Freud, ever attentive to artists’ anal phases, noted in a letter to Stefan Zweig dated 25 June 1931 the fascination musicians have with “intestinal noises,” suggesting this attraction springs in part from an “anal investment” of libidinal energy. More broadly, in Freudian terms, musical expression is the ultimate product of the “dream-work”: the unconscious’s nocturnal enactments rendered audible through sound.

On that premise—whether one embraces it or not—the realm of the piano Fantasia stands as the purest embodiment of Mozart’s “dream-work,” beyond even his operatic achievements. Here the “control game,” as Freud called it—the playful struggle to master an internal object (for Freud, the oppressive figure of Leopold, the archetypal father-master)—finds its fullest outlet in improvisatory prowess. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Fantasia in D minor, K. 397 (what a contrast Mozart’s use of this key presents to Beethoven’s later treatments!), which, befitting any true ludus, remains unfinished—a perfect embodiment of the iocus, the ostensibly “trivial” nothing. Yet in performance it reveals nothing improvised: in just under six minutes, it unfolds with such perfection that it seems preordained, a compact interplay of light and shadow.

The same dream-work under control extends to the other minor-key Fantasia, the C minor K. 475—also, curiously, dedicated to Thérèse von Trattner and composed on 20 May 1785. If you wish to grasp how Mozart rode waves of passion, fell victim to desire in its broadest sense, and yet sought to regiment—and even discipline—that force through a codifying process, this Fantasia offers a vivid testament. Its enigmatic Andantino acts as the springboard for the “Più allegro” missile, which detonates into a dozen ferocious bars where sublimated eros, laced with remorse, erupts in a shimmering vomit of thirty-second notes that literally takes one’s breath away.

Carmelo Giudice’s program closes—faithful to the CD itself, excluding the two downloadable digital bonus tracks (the Marche funèbre du Signor Maestro Contrapunto, K. 453a, and the Sonatensatz in G minor, K. 312)—with two works: the Rondo in A minor, K. 511, and the Adagio in B minor, K. 540. One might well hear them in the light of Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I, since both pieces distil a dramatically shifting affect that moves from depression to a kind of titanically wrought empathy. It is for this very reason that some critics maintain Mozart here already stood at the threshold of the impelling needs that would culminate in Romanticism—most notably in the music of Franz Schubert.

Note their dates of composition—1787 and 1788, respectively—at the very apex of the Salzburger genius’s existential Untergang. The path is marked by symbols, riddles, veiled or overt allusions and allegories cast into the air like I Ching oracle-casts or Mallarmé’s dice, evoking a depth and desolation that astound—and wedge themselves into that interval between The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni, between the promise of a future and its immediate defacement, between the dawning awareness of psychological fracture and its ultimate transfiguration in the final Requiem, with all its disillusionments and inevitable sufferings. How brief was the life of Mozart finally come of age!

Listening to—and relistening to—this recording, I could not help but progressively admire the interpretive vision realized by Carmelo Giudice, who, it’s worth noting, had first conducted meticulous research into the original versions of these works—most notably through a careful analysis of the autograph manuscripts, where available, of course. The italics around progressively underline that only through a process of speculative engagement can one truly fathom the depth and beauty of his interpretation. After all, listening is akin to walking, and “to walk” is one of the most philosophical verbs in existence (the Latin progredi stems from pro- meaning “forward” and gradi meaning “to step” or “to walk”).

The Sicilian pianist’s “interpretive walking,” his very progredi, pointed him toward two precise domains of exploration: what I like to call the “psychological” and the distinctly “technical,” whose union has yielded a definitive recording of Mozart’s minor-key piano repertoire. That Giudice chose—if not to impose a psychoanalytic framework on my analysis, then at least to embrace an introspective perspective—derives from his ability to illuminate what Darth Vader himself would have adored: the “dark force” permeating a facet of the Salzburger genius’s output, a force whose mechanics can be examined even “clinically,” without casting the term itself in a negative light.

This means that, in my view, Giudice has succeeded in surfacing that creative impulse—at once constructive and destructive—by which Mozart alone could reconcile opposites. His pianism here rests not so much on the printed score as on agogic choices, timbral nuances, pedal technique and expressive breath (the “operatic-cantabile” that so often rescues one from a tight corner), all underpinned by painstaking depth of insight—an act of true immersion. Before donning the performer’s mantle, our interpreter was first an archaeologist (much as Giuseppe Sinopoli or Sigmund Freud, by trade or passion), endowed with an uncanny ability to unearth and disentangle Mozart’s writing.

Crucially, though, Giudice never yielded to the easy, banal temptation of leading Amadé onto the analyst’s couch—risking a cold, purely analytical reading. Instead, he mediates the psychical dimension shrouded in the minor key through an exalted musicality, ever aware that when Mozart surrendered to his mental masturbations, he did so knowing his private reveries would be laid bare before the public—above all the Viennese—demanding a communicative transference rooted in pleasure, fascination and seduction. And that is exactly what Carmelo Giudice offers: a profoundly insightful, at times deliciously ruthless interpretation—be it surgeon’s scalpel or dentist’s drill—through which he probes, explores and sutures, yet never forgetting that even the most unsettling, diseased or embarrassing aspects can be conveyed with such delicacy, sensitivity and melodiousness that one is irresistibly drawn to re-listen to what one thought already known.

Gianluca Abbate has done an outstanding job in sound capture, allowing the Steinway Model D 274 used for the recording to reveal all its timbral and dynamic nuances. Above all, through his performance Carmelo Giudice sought to restore a crystalline clarity of tone that evokes—not in a strictly philological sense but in a “historic-psychological” one—the meeting point of harpsichord and fortepiano. The dynamic range is swift, energetic, and invigorated without ever sounding forced, while the reconstructed soundstage places the instrument squarely between the speakers at a healthy depth, so that the sound is appreciated both in height and breadth. The many contrapuntal passages—worthy of the late Mozart—are highlighted by a superb tonal balance, with the mid-low and treble registers always distinct and well-defined. Finally, the level of detail lives up to expectations: the piano’s physical presence projects a pleasingly tactile, almost three-dimensional image.

Andrea Bedetti

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Masterpieces in Minor Key

Carmelo Giudice (piano)

CD Da Vinci Classics C01028

Artistic rating 5/5

Technical rating 4,5/5