Record of the Month December 2025

If there ever was a composer who tackled a given musical genre only once he was sure he could master it completely, without reservations or doubts, it was certainly Johannes Brahms. Every creative step he took was marked by humility (a humility directed at art, seldom at people), born of a wisdom that showed itself from his youth, even before the fateful encounter with the Schumann’s household. If the piano and its compositional offshoots were from the start his daily bread, the same cannot be said for other instruments and other forms of creative application. Consider that the Hamburg genius decided to take on the symphonic genre (and with what results!) only after chewing and digesting it for more than twenty years — such was the time it took for the First Symphony to bloom, begun in 1855 and completed in 1876, having first passed through the service door represented by the two Serenades for small orchestra (composed between 1857 and 1859) and the Variations for orchestra of 1873.

Wisdom, then, but also great severity and ruthless self-criticism, traits he carried with him even after his permanent move to the pleasure-seeking Vienna, inherited from that Hanseatic and Lutheran stamp—at least on an anthropological level—that accompanied Brahms like a second shadow throughout his life. And what held true for the symphonic genre likewise applied, instrumentally, to the violin; if one regards as a venial sin the not insignificant contribution—the twenty-year-old Hamburg native’s Scherzo—to the collective Sonata F.A.E. of 1853, produced by the celebrated Brahms–Schumann–Dietrich partnership and dedicated to Joseph Joachim, our composer did not undertake the real creative elaboration for this bowed instrument until he was forty-five, when he published the D major Concerto, Op. 77. Thanks in part to the resounding success of that memorable work, Brahms rolled up his sleeves and set in motion the project that produced the three violin sonatas, an indispensable pillar of the chamber-music history of the Western art-music tradition (not forgetting that the Hamburg native did produce two other sonatas which, after revisiting them, he destroyed because he was dissatisfied not so much with their substance as with their form, in keeping with his already noted and merciless self-criticism).

Thus, at the very moment when Brahms’s creative flame for the symphonic genre was put on pause after the publication of his first two gems, the insistent, seductive call of chamber music reasserted itself. Within a crucible spanning a decade, between 1878 and 1888, the three sonatas in question took shape: the First in G major, Op. 78; the Second in A major, Op. 100; and the Third in D minor, Op. 108 — sculpted by the great composer respectively between 1878 and 1879, in 1886, and in 1888. These pages have, over time, naturally become a source of inspiration and of numerous recordings for violinists and pianists, to which the names Alessio Bidoli and Bruno Canino are now added; they have committed their own interpretation to disc for the Warner Classics label, a reading that wisely and, in my view, necessarily includes as the final audio track Brahms’s Scherzo from the aforementioned collective Sonata F.A.E.

The artistic clarity that characterized his aesthetic vision made Brahms understand from the start that the dialectical relationship between violin and piano should, while moving beyond Beethoven’s lesson, abandon both the idea of privileging the bowed instrument over the keyboard and a compositional “trademark” aimed at showcasing virtuosity. Instead, he pursued a discourse and melodic line to be expressed on equal terms by both instruments, born of an exquisitely lieder-like atmosphere; from this grew the critical reading that sees these three masterpieces as fundamentally “vocal” rather than purely instrumental. After all, one need only consider Sonata No. 1, known as the Regen‑sonate or “Rain Sonata,” which draws on a fragment of the Regenlied, Op. 59, written fourteen years earlier. That fragment not only appears fully in the sonata’s third and final movement, the Allegro molto moderato, but also fleetingly in the work’s opening — in the very first bars of the Vivace ma non troppo — and it never ceases to hover over the piece’s entire arc, aided by Brahms’s characteristic penchant for variation and the transformation of thematic cells.

I have always pictured the lyrical intimacy that emanates from the Hamburg master’s pages as an animal licking its wounds in the hollow of its den, exiled from the surrounding nature and unable to engage constructively with other members of its species. Intimacy as pain, intimacy as the impossibility of accepting and being accepted — intimacy, then, as a pure barrier to living one’s inner world to the fullest, at the height of an exalting and disturbing solitude in which dream replaces the reality of things. Thus, listening to the reading by the Bidoli & Canino duo of this first chamber monument, one almost seems to touch that supreme solitude, in which the vocalism/instrumentalism pairing is replaced by a sweet lament from which the plug of existence is pulled so that the whirlpool of immanence can embrace everything. The Milanese violinist never yields to sterile sentimentality (this is evident from the wrenching first movement of the Sonata), and without ever tearing at the melodic line he is methodical in fruitfully exploring the possibilities that Brahms’s writing always offers the performer. Canino, who has few equals even on the international stage with regard to these three works, not only follows but continually points the way, as his contribution to the second movement of the First Sonata demonstrates, allowing his younger colleague to set nearly perfect tempi that raise the level of pathos and lyrical saturation to the point of calmly accepting the ocean of melancholic sorrow that fills this moment. The third movement, rich with the lieder-like theme, in this duo’s performance is not yet a “song,” but following the same thread it becomes a kind of dance in which there is only one dancer who moves as if the other presence were there to form a pair. The sound Alessio Bidoli produces at times is almost congealed, without ever fracturing the melody as it rises and falls, perhaps with the precise intention of conveying an idealized sob, while Canino’s piano presses him relentlessly, as if to say that the dream must always collide with the bitter cup reality forces one to drink.

If these three Sonatas are to be heard not only with the heart but also with the mind, then one must understand how, progressively, the “progressive” Brahms (not only in the Schoenbergian sense) files down, sands, and polishes the volumetric relationship between violin and piano; proof of this is Sonata No. 2, Op. 100, whose composition undoubtedly reflects the atmosphere of the place where it was written — among the imposing Swiss mountains that overlook and guard the village of Hofstetten, which looks out onto the equally magical Lake Thun (for this reason Sonata No. 2 has been nicknamed the Thun Sonata).

This volumetric balance, increasingly evened out so as to exalt to the highest degree the lyricism and intimate dialogue between the two instruments, is felt most forcefully in this Sonata, which exudes lieder‑like qualities from every pore and, by virtue of that trait, finds an ideal kinship with the Schubert‑Mendelssohn tradition. In the first movement, an Allegro amabile, several thematic prompts—or at least developmental cells—derive from earlier Brahms Lieder, such as Wie Melodien zieht es mir leise durch den Sinn (“Like melodies something drifts softly through my mind”) and Komm' bald (“Come soon”), the concluding point of the Lied Immer leiser wird mein Schlummer (“Ever lighter grows my slumber”), works that enjoyed great success in part thanks to the voice of the young mezzo Hermine Spies, a refined interpreter of the German Lied repertoire and of Brahms in particular.

Canino’s rounded, dry piano timbre and Bidoli’s impassioned violin speech, tinged with a soft nostalgia, form the counterpoint to their entire reading, with choices of tempo and communicative texture that highlight the sovereign volumetry of the composition, calibrating entries and their density as the result of technical articulation and an expressivity that never yields to sentimentality for its own sake.

This search for volumetric perfection and balance between the parts — which lets themes, developments and recapitulations bloom along a melodic line that is never banal but always rich and engaging — seems to have been set aside by Brahms in his third and final Sonata, the one that cost him the greatest effort and, concurrently, the doubts and anxieties fed by his habitual merciless self‑criticism (attested also by a letter he sent to Clara Schumann), shortly before the work was published, as always, by Simrock. The D minor Sonata likewise came to light over the course of three summers, from 1866 to 1868, in Thun, and what critics of the time immediately noticed was that the great Hamburg master had yielded to the seduction of virtuosic appeal (a point that applies above all to the role assigned to his beloved piano), tipping the balance in favour of the keyboard over the violin.

Moreover, unlike the first two Sonatas, here intimacy, lyricism and the calm conversation between two friends given to nostalgic recollection give way to an exuberance, a vitalism that reads as a sudden existential jolt before it is an artistic one. When the Sonata was completed, Brahms still had nine years to live, many of them experienced within the downward arc of an Untergang that leaves little room for a future or for a Nietzschean “will to power,” and more for a progressive letting‑go, sharpened by the death of his beloved Clara. Admittedly, there would be a curiosity that turned into a brief, enthusiastic interest in the clarinet, but his retreat was dictated above all by a renewed devotion to the ever‑cherished piano, which in his very last pages takes on the contours of a true “sonic diary/testament.” Thus, the Brahms of the Third Violin Sonata briefly dons the “vitalist” guise of a Bergson transposed into music and presents itself in a more canonical four‑movement layout that allows for a greater diffusion of themes and of the composer’s creative needs.

We were speaking, then, of a kind of “betrayal” of the volumetric balance between the two instruments in favour of a Drang edged with virtuosic contribution (an aspect that, in concert life, has tended to make this Sonata prevail over the two earlier ones). Yet it is equally true that behind the clarity and charm of the melodic lines that fill this composition still lies the seed of experimentation happily brought to a solid harmonic and structural achievement, since here too the concept of variation and the methodical, relentless exploitation of every thematic cell is carried out exemplarily by the German composer, a fact that later drew Schönberg’s interest in his study Brahms der Progressive.

Moreover, as in the first movement, an Allegro, there is the ability to marry the idea of “instability,” supplied by the piano’s rhythmic drive, with that of “stability,” asserted by the violin’s melodic line — which at first glance gives the impression of two Euclidean lines destined never to meet, but which, on closer listening, reveal a continual mutual chiselling that expands the timbral range of both instruments to the point that at times one senses a genuinely “symphonic” hue.

The exquisitely chamber-music rush occurs in the Adagio, one of Brahms’s melodic pinnacles, where the violin becomes a kind of suction pump capable of almost entirely absorbing the sonic space. And if the lively intermezzo that follows is a sort of brilliant appetizer preparing the listener for the finale, the Presto agitato, the latter ideally represents the composer’s sovereign ability to manipulate sound material, with the piano taking the violin by the hand and drawing it into an extraordinary Chorale.

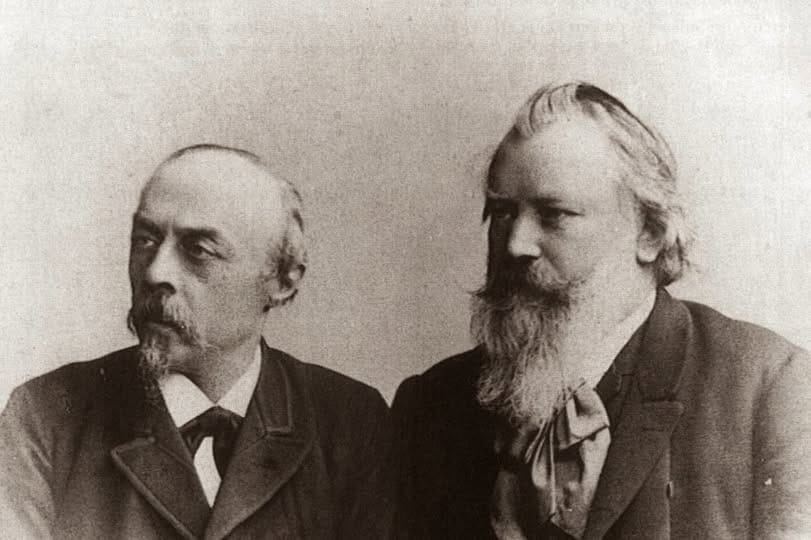

I believe that it is precisely the Bidoli & Canino duo’s reading of this final Sonata that can confirm the overall success of the triptych; their interpretation brings to the surface not only the individual dimension of each composition, highlighting its proper stylistic and expressive traits, but above all the general choral quality through which Brahms conceives and signs the chamber‑music genre itself. Thus, this disc becomes an exhilarating listening journey through which one can perceive the true scope of the Hamburg master’s intentions. Moreover, let us not forget that we are witnessing the meeting of two interpretive generations (there are more than fifty years’ difference in age between Bidoli and Canino!), which offer different perspectives and sensitivities that fruitfully combine and mutually enrich one another in the exploration of the Brahmsian multiverse, with the wisdom of one joining the freshness of the other. Their performance of the Third Sonata in particular shows how Canino’s firm, rounded pianistic experience supplies Bidoli’s expressive exuberance with the sonorous carpet so necessary to bring to life a score in which enthusiasm and awareness happily coexist, since, as never before, in this composition the now‑aged Hamburg master, turning to his past, smiles at the memory of the young, charming Brahms, with his cerulean eyes, timidly knocking for the first time at the Schumann’s door.

“Record of the Month” for December by MusicVoice.

Mario Bertodo handled the sound capture, and the result is overall good. What strikes immediately is undoubtedly the dynamics — very fast and vigorous — yet at the same time free of inappropriate colours (the instrument used by Alessio Bidoli, a 1902 Stefano Scarampella, produces a sound nothing short of sumptuous and powerful, especially in the bowing).

The soundstage places the two instruments on a very close plane, which sometimes leads to a slight reverberation, particularly when the violin reaches its high and ultra‑high registers, but this does not compromise the authenticity of the sonic image, which radiates both vertically and horizontally. Likewise, the tonal balance appears correct, with faithful reproduction of the high and mid‑low registers by the two instruments, neither prevailing over the other.

Finally, the level of detail is extremely tactile, with a three‑dimensional presence for violin and piano, set against a deep black that helps reinforce the physical immediacy of both.

Andrea Bedetti

Johannes Brahms – The Violin Sonatas

Alessio Bidoli (violin) – Bruno Canino (piano)

CD Warner Classics 5021732868572

Artistic rating 5/5

Technical rating 4/5