Album of the month: February 2026

There are certain recording projects that, beyond their artistic merit, allow the more attentive, sensitive, and naturally more cultured listener to grasp aspects that extend far beyond the realm of the sonic element itself. The album I am discussing in this contribution, released by Da Vinci Classics and featuring several world-premiere recordings, represents a perfect example of this. I am referring to the CD Cantatas: Sacred Music in Thuringia, which presents sacred works by the obscure Fr. Troll, Johann Gottfried Walther, Johann Theodor Roemhildt, Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, and an anonymous flute concerto based on a copy by Johann Georg Pisendel. These pieces are historically situated in the first half of the 18th century within the geographical region of Thuringia, located in the central heart of Germany. As noted by musicologist and conductor Marcello Trinchero—who conducts the vocal and instrumental members of the ensemble I Contrappuntisti on this recording—this region should not only be remembered musically as the birthplace of Johann Sebastian Bach, but also as home to "a multitude of composers—some renowned in their time, others later relegated to obscurity—whose works bear witness to the extraordinary vitality and diversity of the period."

To understand the significance of these authors, the so-called Kleinmeister (minor masters) of Thuringia, and their music—rooted in the strict rigor of Lutheran theological dialectics—one must take a step back, approximately two centuries earlier. This was when this vast territory witnessed one of the most brutal slaughters in Western history: the Peasants' War (Bauernkrieg), sparked by the emergence of the Protestant Reformation and its various currents that disrupted the countrysides and cities of the region. While this is not the place to recount those dramatic and mournful historical events, it is necessary to recall how Lutheran doctrine and its offshoots—especially those centered around the even more revolutionary thought and action of the preacher Thomas Müntzer, leader of the peasant rebellion—led the German society of the time to a true grassroots revolt. This caused an inevitable reversal of values that, until then, had favoured the top of the pyramid—a peak represented by conservatism and the exclusive privileges of the nobility and high clergy. In this sense, the Protestant revolution—committed to spreading anti-papal views and challenging the absolute power of the few (Müntzer’s motto was omnia sunt communia, or "all things are common")—did not limit itself to making the Holy Scriptures accessible to the humble and dispossessed, as with the German translation of the Bible (Bibelübersetzung). Rather, it allowed them direct, leading involvement in religious and social life through the emotional and imaginative power of music. This enabled the faithful to be not merely passive observers of ecclesiastical rites, but above all active participants within the sacred music performed in the churches of the time.

Precisely in the name of this active, effective, and engaging co-presence—in which the unlearned and ignorant faithful finally felt like protagonists, like bricks forming a solid wall—the sonic dimension acted as a formidable adhesive. It allowed the community to better understand the representational dimension of the world into which, in a Heideggerian sense, its members had been "thrown." Thus, even the most humble, humiliated, and rejected participants began, through the formulation of sounds, to better perceive and focus on a Vorstellung (representation) of their own in which they could recognize themselves.

The seed had been sown, and it was capable of blossoming into a plant thanks to the resilience of its roots, even after the fierce and terrible repression that took place in Thuringia after 1526, following the end of the deutsche Bauernkrieg and the execution of Müntzer, who was beheaded the previous year, on May 27, 1525. This new faith, bolstered by the powerful contribution of music, ensured that the less affluent classes—those socially most exposed to arrogance and abuse—could recognize themselves within the dimension of community (Gemeinschaft) to resist the jarring and disturbing projection of society (Gesellschaft). In light of this, the listening and study of works belonging to the vast corpus of sacred music that emerged from the second half of the 16th century and radiated throughout Central and Northern Germany in the 17th and 18th centuries must be metabolized with these historical and religious aspects in mind.

Now, returning to the Da Vinci Classics album in question, it is interesting to note that this recording project was fundamentally born from a discovery—as Trinchero himself explains in the liner notes—which took place in 1968 during the restoration of the church in Großfahner, a village located about twenty kilometres northwest of Erfurt, the capital of Thuringia. At that time, a cache of approximately three hundred sacred works by Central German composers, dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries, was discovered in a roof cavity. Since most of these precious manuscripts were damaged by time and humidity, it was decided the following year to transfer them to the Hochschule für Musik “Franz Liszt” in Weimar for cataloguing and restoration, where they are still preserved today.

Beyond the works of well-known composers such as Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel and Georg Philipp Telemann, many other manuscripts were written by other musicians—specifically the aforementioned Kleinmeister of Thuringia—who were either entirely marginal or previously unknown. This is the case with the so-called “Herr Troll”; besides the seven cantatas preserved in the Großfahner/Eschenbergen collection, we only know of one other cantata located at the Göttingen University Library and a violin concerto held at the Münster University Library. The composer’s first name remains completely unknown; we only know, from the title pages of his works, that it can be deduced it began with “Fr.”, possibly Friedrich.

Based on the very limited material that has reached us and considering what was stated above, it is impossible not to highlight how Troll’s musical vision is exceedingly severe, exquisitely imprinted with a North German style that shares affinities with that of Dietrich Buxtehude. Consequently, it is evident that in his works, every form of ornamentation—typical of Southern German music influenced by the Italian school—is banished. Furthermore, Troll relies on the so-called durchkomponiert (through-composed) structure, in which repetitions, strophic forms, or separate sections are eliminated, with the music following the text or dramatic action continuously and without the use of recitatives.

The album’s tracklist includes two of his works: the Christmas cantata Siehe ich verkündige euch and the Easter cantata Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied. Trinchero rightly points out how Troll’s compositional conception can be considered idiomatic, so to speak: in the first cantata, descending melodic lines evoke the divine force descending among men, while in the second, ascending movements lead the listener to rise and identify with the concept of the Resurrection. This demonstrates how his music was fruitfully “theological,” “scenically” reinforced by the use of trumpets and timpani.

In addition to the works dedicated to Cantatas—beyond those by Troll and Johann Theodor Roemhildt, as I will discuss later—the program offered by this recording also includes four instrumental pieces: namely, a flute concerto by an anonymous author from the first half of the 18th century (originally conceived for violin and preserved through a copy by Johann Georg Pisendel), and three Chorales for solo organ, two by Johann Gottfried Walther and one by Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow. The flute concerto is structured in three movements and exhibits a style that calls to mind the brilliance and liveliness of Vivaldi’s concertos. This explains the interest shown by Pisendel, who was one of the most prominent violinists of the time in Germanic lands.

The Leipzig-born Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow (1663–1712), after studying organ and composition, was appointed organist and Kapellmeister of the Church of St. Mary in Halle in 1684, a position he held until his death. A prolific composer of sacred works, including cantatas, oratorios, and choral music, as well as the teacher of the young Handel, his music can be traced back to the creative lineage of Dietrich Buxtehude. This is clearly evidenced by the organ chorale Christ lag in Todesbanden, the work that concludes the album.

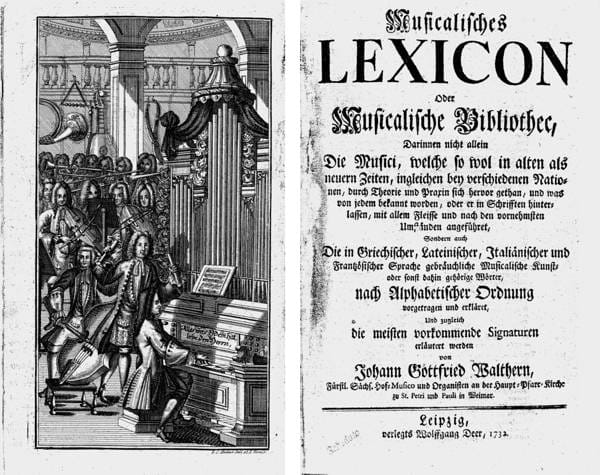

Johann Gottfried Walther was also a son of Thuringia, born in Erfurt in 1684 and passing away in Leipzig in 1748. Beyond his substantial musical output, his fame is inextricably linked to the legendary Musicalisches Lexicon, published in Weimar in 1732—a work that is, for all intents and purposes, the "forefather" of all music dictionaries, in which he compiled biographical data on composers alongside explanations of key musical terms. Furthermore, Walther was a second cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach, with whom he collaborated very actively during the Weimar period, notably transcribing numerous concertos by contemporary Italian composers, including Vivaldi, for harpsichord and organ. As a musician, Walther is rightly remembered for his organ compositions, which flourished during his tenure as organist at the Stadtkirche in Weimar—a post he secured in 1707 and held until his death. His style, a monolithic expression of the Baroque, clearly reflects—as evidenced by the two organ pieces on this CD, the chorales Von Gott will ich nicht lassen and Herr Christ, der einig Gottes Sohn—the undeniable influence of both the indispensable Buxtehude and the more renowned Kantor.

More peculiar and less well-known, at least to non-specialists, is the figure of Johann Theodor Roemhildt, born in Salzungen, near Eisenach, who lived between 1684 and 1756. As the son of a preacher—a fact that influenced his compositional vision—this musician began his musical studies with Johann Jacob Bach (1655–1718), a member of the Meiningen branch of the Bach family. Thanks to his marked talents, he was accepted into the Thomasschule in Leipzig, where he refined a solid musical education under the guidance of Johann Schelle and Johann Kuhnau, while simultaneously continuing his studies at the University of Leipzig. His professional activity was inextricably linked to Duke Henry of Saxe-Merseburg, for whom he became court Kapellmeister. Furthermore, in 1735, upon the death of the court organist Georg Friedrich Kauffmann, Roemhildt also assumed the position of organist at Merseburg Cathedral, a post he held until his death.

Of this musician, who in his time enjoyed greater fame than Johann Sebastian Bach, more than two hundred and thirty cantatas have survived, along with a St. Matthew Passion. These works are distinguished by the brilliant use of the brass section, primarily trumpets and horns. His oeuvre continued to circulate until the final decades of the 18th century, before being gradually forgotten.

Only thanks to the very recent work of two German musicologists, Klaus Langrock and Christian Ahrens, has it been possible to compile a detailed catalogue of his works (designated as RoemV), allowing for a proper re-evaluation. These studies have not only enabled a wider dissemination of his works, at least among enthusiasts of this musical period, but have also helped us understand how his style fits fully into the so-called gemischter Stil—the "mixed style" cultivated by German composers of the High Baroque, resulting from a syncretism between the Italian model and elements of French derivation. Marcello Trinchero chose to include two of Roemhildt's cantatas in the Da Vinci Classics CD: the Cantata Herr Jesu, deiner trost ich mich, RoemV 129, and the Cantata Herr wie groß ist deine Güte, RoemV 201. The former is a very brief piece, a typical feature shared with the composer's other solo cantatas and adopts the elementary alternation of Aria – Recitative – Aria; the latter is significantly broader and more complex, scored for full orchestra with solo tenor, choir, three trumpets, timpani, recorder, two violins, viola, and basso continuo.

After listening to the album several times, I told myself that to appreciate German Baroque works, one does not necessarily need to turn to German recordings and performers; as in this case, Italian musicians and singers are equally capable of bringing the artistic and spiritual Geist of these pages to life in a nearly ideal way. The expressive performance and the reading provided by Marcello Trinchero—whose conducting calibre merges seamlessly with his musicological expertise—and the members of the ensemble I Contrappuntisti is truly moving and engaging. (I must mention, at the very least, tenor Matteo Straffi, bass Marco Grattarola, flutist Valerio Febbroni, and organist Roberto Passerini, alongside soprano Arianna Stornello and contralto Giulia Beatini). Their work is devoted to a truly “anthropological” adherence, capable of restoring the dimension, depth, and the social and religious mission of a musical vision that is nothing short of unrepeatable. While the voices are genuinely convincing in their texture and their ability to convey both sentiment and mystery, the instrumentalists are certainly no less impressive, thanks to Trinchero’s authoritative and lucid direction. He is fully immersed in the Protestant style mentioned earlier and has the undeniable merit of presenting composers and works that certainly did not deserve such unjust oblivion.

MusicVoice Album of the Month – February

The sound engineering, captured by Simone Barbieri and Alessandro Panella in the Church of Ognissanti in Trino (Vercelli), is noteworthy—starting with the dynamics, which offer speed, energy, and a pleasant naturalness (a quality particularly evident in the brass and timpani). The soundstage parameter reveals a reconstruction capable of conveying the spatial depth of the sonic event, while simultaneously allowing the sound to radiate in width and height far beyond the speakers. The same applies to the tonal balance and detail: the former is excellently clean, properly defining the mid-low register from the high register in both voices and instruments; the latter is rich in texture, with remarkable amounts of "black" around the performers, providing three-dimensional credibility and an immersive listening experience.

Andrea Bedetti

Various Authors – Cantatas: Sacred Music in Thuringia

I Contrappuntisti – Marcello Trinchero (conductor)

CD Da Vinci Classics C01098

Artistic rating 5/5

Technical rating 4,5/5