What would become of a composer’s creation if there were no performer to bring it to life? Certainly this is a rhetorical, if not pleonastic, question, but it’s one worth asking from time to time so we don’t forget that, as music history teaches us, the transitive process leading from the written sign (the composer) to the audible sound (the performer) is not merely a necessary concatenation, but also an act of affinity—an ideal communion between the one who creates and the one who re-creates. Recalling Goethe’s admonition that we should never ask our listeners whether they agree with us, but rather whether they follow the same path, we see that when creator and re-creator share that path, a singular whole emerges: an artistic act that is complete, coherent, circular rather than linear.

That the meeting of German composer-lutenist-guitarist Hans-Jürgen Gerung and guitarist Andrea Monarda perfectly embodies Goethe’s vision becomes abundantly clear upon listening to the new EMA Vinci release Andrea Monarda plays Hans-Jürgen Gerung. On this album, the Puglian virtuoso interprets several solo-guitar works by the German musician—specifically …und bleibst so lang ich bleibe da Hölderlin im Turm, Lichtpunkte, La commedia dell’arte, and Fraginesi—offering the listener a precise insight into the aesthetic conception of someone who was first a pupil and later a friend of Sylvano Bussotti.

As Renzo Cresti, Italy’s foremost specialist in contemporary music, recalls in the liner notes, it was Gerung himself who explained that “there are different ways to cross the Alps—on foot, by car, or by plane; on this CD we cross them through the power of music. Andrea Monarda is an artist with a deep affinity for art and culture from across the Alps. It was his idea to record an album with a selection of my most important works for guitar. The result is a congenial collaboration between an Italian virtuoso and a German composer.”

In other words, the “power of music” brings to fruition a project in which two sensibilities—separated by what might seem an insurmountable barrier, the Alps, but which symbolically stand for all the forces that relentlessly divide us along life’s trajectories—can identify with one another, each becoming the other’s emanation, testament, and resonance chamber.

Here, that identification is truly total and absolute, guided by a beneficent δαίμων that perpetuates the transfer between Gerung and Monarda in the act of re-creation. Monarda, it’s worth noting, is no stranger to the notion of “trans”—he graduated from the Faculty of Interpreters and Translators at the University of Trieste and is himself an active translator. Moreover, when one considers the very nature of the pieces on the album, it’s clear that in crafting his scores Gerung effectively “translated” poetic elements (Hölderlin), landscapes (Lichtpunkte), theatrical motifs (La commedia dell’arte), and geographic inspirations (Fraginesi) into music—enabling Andrea Monarda to embark on a Euclidean/translational process: a sonic trajectory that, in moving from its point of origin to its destination, dissipates inexorably through space and time.

There is another aspect to consider—one already present in Gerung’s works beyond the realm of the guitar—which concerns his sonic trajectory as it radiates into the spatial dimension where it unfolds. This trajectory, often shaped by other artistic expressions—above all painting, of which the German musician is both passionate connoisseur and accomplished painter and draftsman—rarely adopts an assertive, conclusive, or self-proclaiming stance. Instead, it is devoted to an incessant, tireless need to ask, to question, to probe with the timbre of the instrument what surrounds it, in order to understand and embrace it. That act of questioning—from subject to object—reveals itself most fully when performed on an instrument like the guitar, whose strings enable this reiterative process. The resulting sound is never convulsive, ostentatious, or thrown in the listener’s face; it remains respectful and conscious of not embodying an “answer.” For this reason, engaging with Gerung’s scores demands an equally iterative listening, one repeated over time, to align oneself with this interrogative process, which descends like a transparent film over the objects it observes and attempts to “decode” (we always keep the translational dimension in mind…).

Beginning with the piece dedicated to Hölderlin’s poetics, we encounter what amounts to an impossible love—like that between Susette Gontard, mother of the child tutored by the German poet, and Hölderlin himself—a question inherently without answer. Does not the very title …und bleibst so lang ich bleibe (“…And you remain for as long as I remain”) embody something perpetuated through the image of the other, so long as one wishes to sustain it? This enactment is almost impalpable, diaphanous, at the very edge of transparency, translated into sound by Gerung through an equally delicate, hesitant approach. It tragically evokes Rimbaud’s “par délicatesse, j’ai perdu ma vie” or, even more fittingly, Yukio Mishima’s aphorism “the perfect love is the one that never comes to fruition.” Here, the German composer appears particularly drawn to what cannot be realized, cannot manifest openly, cannot declare itself candidly to the world. A close look at his drawings confirms this: they are dominated by a few essential strokes that allow non-matter to become barely matter—like a love whispered only to slip through the fingers. On this basis, the musical structure that unfolds over more than eight minutes in this piece can only assume an almost Bergman’s flavour of timbral whispers concealing suppressed cries—nuances shaped and moulded by Monarda—in which the attempts of a sentiment predestined for nothingness struggle to emerge.

If love can become an insurmountable obstacle when it fails to unfold according to our plans and expectations, then so too can a barrier offered and imposed by nature—such as a mountain range—become, in Gerung’s creative realm, the catalyst for “translating” aspects that appear hidden and falsely concealed.

The second piece, Lichtpunkte, divided into three movements—Calmo, Senza tempo, Poco energico—aims to depict the Swiss mountains precisely in this way: the “points of light,” as the title suggests, are those reflected in the darkness of night and their transformation throughout the day, symbolizing the perpetual transmutation of things even within their natural immovable state. This evokes an almost Heraclitean resonance in the interplay of mobility embedded in stillness, with the guitar becoming a vehicle of immanence that launches glimmers of transcendence into the air.

Now the balance shifts: the scale that formerly bore the weight of the German Geist’s cultural and natural call now tilts toward the tribute Gerung pays to Italian popular art and culture. Italy is undeniably his second homeland, the living embodiment of the grand tour to which German expressive genius ventured in the nineteenth century—crossing the Alps to cast itself into the arms of Mediterranean sunshine and the cradle of classical antiquity. Thus emerges the cycle La commedia dell’arte, whose legacy brims with fantasy: a fable enacted on an improvised stage—whether a village square or a modest playhouse—becomes a landing point in the labyrinthine and absurd edifice of contemporary theatre, a rupture of hope, the finale of a game never begun.

In this cycle, the typical regional masks of Italian folk theatre—Colombina, Arlecchino, Pagliaccio, Pantalone, and Il Capitano—are introduced by a Prologue, separated by four Intermezzi, and concluded by an Epilogue. Here, Monarda’s guitar transforms into a six-string Fregoli, its timbral fabric dissecting the theatrical physiognomy of these five characters, responding to the sudden variations dictated by their psyches and traits.

Finally, Fraginesi, divided into four parts—Garden, Dogs, Oven, Silence. Fraginesi is a small Sicilian village about fifty kilometres from Palermo, home to a typical farmhouse surrounded by olive and fruit trees. This place left a deep imprint on the German composer-guitarist, who chose it in this piece as the very symbol of the Mediterranean spirit that draws men whose blood still carries an alpine memory. From this origin, the South is seen through the eyes of a child: an expansive, boundless stage no longer populated by imaginary characters but by real ones—scents, flavours, emotions that inevitably stretch the senses and grasp everything to transform it into feeling. These sensations dominate the final piece, where Andrea Monarda’s Mediterranean sensibility overlaps with and guides the one evoked by Gerung, in the role of a modern-day Dante.

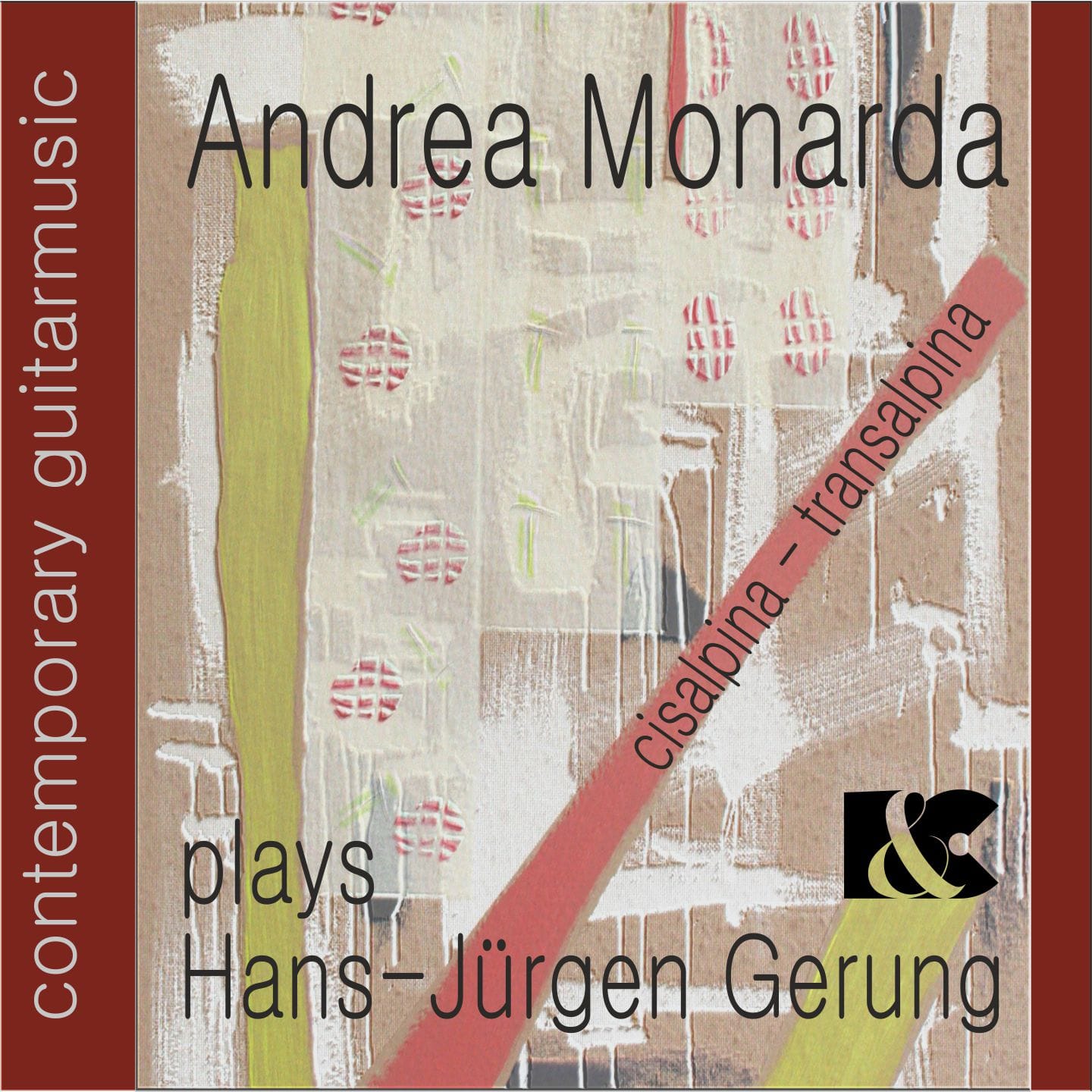

On the CD cover there is a contemporary abstract painting whose author remains unnamed, yet it perfectly captures the spirit and soul of this recording. Delicate patches of colour are dominated by bold strokes of white, which embrace a diagonal red stripe bearing the words “cisalpina – transalpina.” To me, this image perfectly conveys the essence of the album, as if it were a sonic Tagebuch aus Italien—a traveller’s enchanted gaze, in the spirit of Leskov, marrying his profound native culture with that of a second homeland, through which he continues his work as a “musical translator.”

The sound was captured by Mimmo Galoppa, who managed to record the tones of Monarda’s three guitars exceptionally well, thanks to a highly appreciable dynamic range, a soundstage that places the instruments centrally and up close without distortion, and a tonal balance and level of detail free of any flaws.

Andrea Bedetti

Hans-Jürgen Gerung – Andrea Monarda plays Hans-Jürgen Gerung

Andrea Monarda (guitar)

CD EMA Vinci 70378

Artistic rating 5/5

Technical rating 4/5