The history of early music—spanning roughly from the 13th century to the dawn of the Baroque—reveals a crucial point: the dissemination and transmission of musical knowledge occurred not through the individual figures of the musicians themselves, but through the venues where they primarily operated. This was a necessity for a very simple reason: the artists of the era lived in the shadow of their patrons—be they sovereigns, wealthy aristocrats, or high-ranking prelates—who were willing to protect and sustain them in exchange for their musical services.

We must remember that, at the time, the status of a musician was akin to that of any other subordinate—one duty among many in the service of a lord or powerful figure. Such a ruler might be an enlightened connoisseur, captivated by the power of artistic expression to the point of being considered a true patron of the arts; conversely, he might regard painting, music, and dance as mere pastimes—pleasant diversions and nothing more, on par with the divertissements of court jugglers and jesters.

One of the places where music was cultivated with love, interest, and profound engagement was undoubtedly the Gonzaga court in Mantua. Here, a particular instrument—the most celebrated of the High Renaissance—found its home: the lute. In truth, the lute’s trajectory lasted much longer, spanning exactly five centuries from the Middle Ages to the second half of the 18th century, serving as an emblem and symbol of the most exquisite musical refinement.

It is precisely to this Renaissance lute repertoire and its prolific presence at the Mantuan court of the Gonzaga that one of the world’s leading lutenists, Massimo Marchese (hailing from Alessandria), has chosen to pay tribute in his latest recording. Released by Aulicus Classics under the evocative title Quanta beltà: Lute Music from Gonzaga’s Court, the album features twenty-four pieces for the instrument by various composers of the era, including Pietro Paolo Borrono, Francesco da Milano, Marco da L’Aquila, Francesco Spinacino, Joanambrosio Dalza, Vincenzo Capirola, and Leonardo da Vinci.

In the concise liner notes accompanying the album, Massimo Marchese provides further insights that clarify how and why the Renaissance became the "golden age" of the lute. This began with a fundamental shift: during this period, musicians transitioned from using a plectrum to plucking the strings with their fingers. This shift significantly expanded the palette of timbral and expressive possibilities, allowing players to perform multiple voices simultaneously and weave together harmonies that were as complex as they were elegant.

Furthermore, the instrument itself underwent a technical evolution with the addition of a sixth course, which extended its range to three octaves. The impact of the advent of music printing was equally transformative. In 1507, Ottaviano Petrucci published the first printed books for solo lute in Venice, dedicated to the music of Francesco Spinacino; these were followed shortly after by the collections of Giovan Maria Alemanni and Joanambrosio Dalza. This facilitated a wider dissemination and appreciation of lute music, reaching an increasingly large audience of enthusiasts.

Among the various musicians and composers featured by Massimo Marchese in this latest recording, several merit special mention to understand their significance, beginning with Vincenzo Capirola. His work has survived thanks to one of his pupils, Vidal, who—fearing his master's music might be lost—compiled a manuscript around 1517 (now held at the Newberry Library in Chicago), adorning it with splendid miniatures of animals, flowers, and scenes of daily life. These decorations were not merely driven by aesthetics; they served to make the volume so beautiful that no one would ever have the heart to discard it, thus safeguarding Capirola's music for posterity. Capirola was a composer capable of introducing techniques that were pioneering for the time, such as the use of vibrato and dynamic markings (namely "piano" and "forte"). From this Lombard musician, Marchese performs the Recercar primo and La Vilanela.

Another tutelary deity of the lute was Marco da L’Aquila, a musician who served as a bridge for his instrument between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. A true virtuoso, he was the one who introduced the imitative polyphonic style, through which he managed to make it seem as though multiple musicians were in dialogue, when in reality only one was performing. Marchese executes three pieces by this artist: two Ricercari (No. 30 and No. 33) and La cara cossa.

Massimo Marchese devotes significant space to a character who is nothing short of enigmatic—a sort of "Caravaggio of music" due to his adventurous and murky life: the Milanese Pietro Paolo Borrono. In addition to being an exceptional lutenist—to the point that his works were published alongside those of the "divine" Francesco da Milano—it appears he was involved in political intrigue and even espionage on behalf of the Spanish government in Milan. Borrono's compositional style is marked by an energetic disposition, dominated by dance rhythms and a virtuosic technique that reflects his exuberant personality, as demonstrated by the four pieces performed by Marchese, including the famous Saltarello della preditta and Peschatore che va cantando.

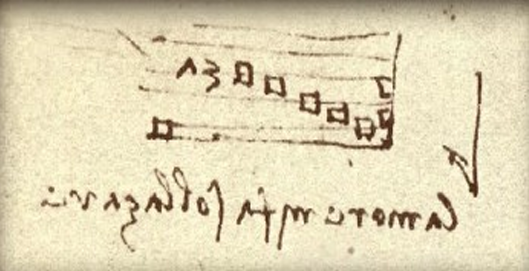

It should come as no surprise that the name of Leonardo da Vinci can be found alongside these great musicians. Beyond being the brilliant inventor and painter, we all know, he was also a virtuoso of the lira da braccio. In his notebooks, such as the famous Windsor Codex, one can find genuine "musical rebuses" which the supreme Renaissance genius ingeniously created; by writing a series of notes on a staff, he ensured that when read as a score, they would give life to phrases or mottos. In the album's tracklist, Massimo Marchese performs the piece 3 Rebus, created by lutenist Massimo Lonardi, who arranged it into a refined and captivating counterpoint work for the lute.

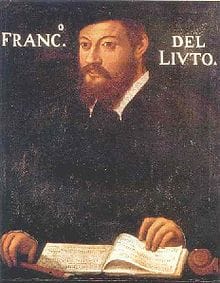

Within this sonic collection, it would have been impossible to omit the figure who must arguably be considered the greatest lutenist of the Italian Renaissance: Francesco da Milano. Born Francesco Canova, he was dubbed "il Divino" (the Divine) by his contemporaries for his unparalleled technical and expressive skill. Such was his fame that his music was printed and disseminated throughout Europe between 1536 and 1603. Specifically born in Monza into a family of musicians, he moved to Rome as a young man, where he served at the papal court for most of his life under four different pontiffs: Leo X, Adrian VI, Clement VII, and Paul III. He was also the lute master to Ottavio Farnese, Paul III’s grandson and the future Duke of Parma.

His output comprises over ninety Ricercari and fantasias, in addition to toccatas and intabulations of vocal works (primarily lute transcriptions of polyphonic pieces by composers such as Josquin Desprez). His unmistakable style is characterized by profound formal balance and the masterful use of counterpoint and polyphonic imitation. He likely died in Milan in 1543 and was buried in the Church of Santa Maria alla Scala, which was demolished in the 18th century to make way for the construction of the Teatro alla Scala. On his CD, the Alessandrian performer presents two refined examples of this composer's great artistry: Ricercare No. 10 and Ricercare No. 33.

What is most striking in Massimo Marchese's interpretation of these twenty-four tracks—performed on a six-course lute crafted by Ivo Magherini and featuring composers of the Franco-Flemish school such as Johannes Ockeghem, Josquin Desprez, Jacques Arcadelt, and Jean Richafort—is the total adherence to the inherent dimension of the music itself. It serves as an ideal vademecum for entering the historical era in which these lute masterpieces were conceived. We must consider that we are still dealing here with an exquisitely abstract conception of sound: pure beauty composed of wondrous sequences that suggest nothing other than their emergence from silence, only to return to it once more.

Yet, if one manages to perceive this sonic philosophy, it is impossible not to be captivated by the performance of the Piedmontese specialist, a passionate witness to an era that must not be forgotten or marginalized. This is for a very simple reason: what we hear on this CD is not merely a tribute to the music of that time, but also a precious reminder. it underscores that without these composers and without the historical and artistic branching of the lute, everything that followed would simply not have existed.

This is one of the most profound and successful early music recordings I have heard in recent years.

Massimo Marchese himself handled the sound engineering and mastering, with entirely commendable results. The dynamics are fast and sufficiently energetic, without any blurring or coloration that would detract from the naturalness of the sound emission. In terms of soundstage, the lute is reconstructed with a fair degree of depth; the instrument is sculpted at the centre of the speakers, with a sound that radiates beautifully in both height and width. Crucial in a recording of this nature is the parameter of tonal balance, which is neither compromised nor distorted, as the mid-low and high registers always remain distinct and properly focused. Finally, the detail reveals a generous "blackness" around the instrument, contributing to its tangibility and three-dimensionality.

Andrea Bedetti

Various Composers – Quanta beltà: Lute Music from Gonzaga’s Court

Massimo Marchese (lute)

CD Aulicus Classics ALC 0157

Artistic rating 5/5

Technical rating 4/5